The Psychology of Creativity: Why Tools Matter More Than Talent

Art is often described as the expression of the human soul. It is a space where rules are meant to be broken, where colors clash, and where imagination runs wild. From the splatter paintings of Pollock to the melting clocks of Dalí, the history of art is full of strange techniques. However, even in the most avant-garde studio, there is a basic relationship between the artist, the tool, and the canvas. This relationship is governed by the physical properties of the materials. You need a tool that can hold pigment and release it in a controlled way.

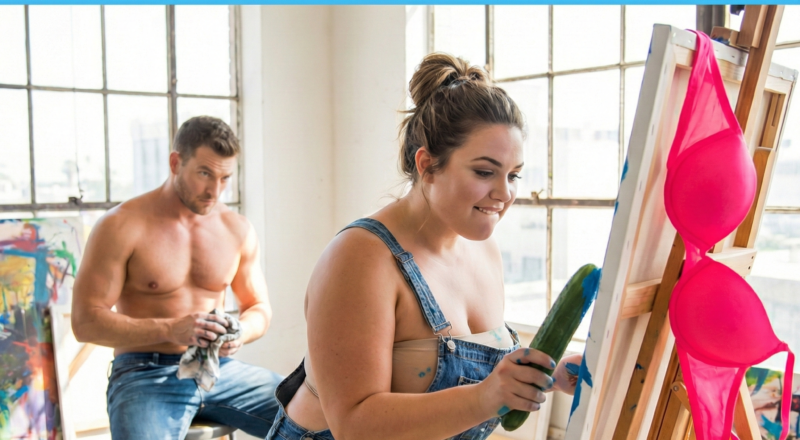

The mistake in this puzzle plays on the blurred line between “artistic license” and “logical failure.” It presents a scene of intense creativity. The lighting is perfect, the artist is focused, and the atmosphere is electric. But if you look past the romance of the scene and focus on the mechanics of the painting process, you will find an object that has absolutely no business being in a studio. It is a humorous reminder that while art is subjective, the tools we use to create it usually need to be functional.

The Creative Process vs. The Cognitive Shortcut

To solve this visual riddle, you need to overcome “Functional Fixedness.” This is a cognitive bias that limits a person to using an object only in the way it is traditionally used. Usually, this bias prevents us from seeing creative solutions (like using a coin as a screwdriver). In this puzzle, the bias works in reverse. We see an object in an artist’s hand, so we assume it functions as a brush. Our brain “fixes” the function to match the context.

Take a closer look at the woman in the foreground. She exudes the vibe of a dedicated painter. She has the messy overalls, the intense expression, and the stance of someone in the “zone.” But follow her arm down to her hand. Look at the texture of the object she is holding. Is it made of wood and bristles? Or is it made of organic matter? Does it have a ferrule (the metal band on a brush), or does it have kernels?

The decoy objects—like the shirtless model in the background or the bright neon pink item on the easel—are designed to act as “visual noise.” They divert your attention to the social dynamics of the room (“Is he her boyfriend? Is he a model?”) rather than the physical reality of the painting action. This distraction technique is essential for a good puzzle; it forces you to consciously redirect your focus back to the details.

The Evolution of Art Supplies

Why does the specific tool matter? Throughout history, artists have used many things to paint: fingers, knives, sponges, and even air. But the paintbrush remains the gold standard because of its unique engineering. The bristles (whether synthetic or natural hair) are designed to hold a specific load of liquid and release it smoothly across a surface via capillary action. This allows for precision and blending.

Replacing this engineered tool with a random object creates a “texture clash.” If you tried to paint with the object in this image, you wouldn’t get smooth strokes. You would get a lumpy, uneven mess. It would act more like a stamp than a brush. While this might be a cool technique for a kindergarten project, it clashes with the serious, realistic tone of the rest of the image.

In the world of professional development, this is a lesson in “Resource Management.” We often try to force a result using the resources we have at hand, even if they are completely inappropriate for the task. It’s like trying to write code in a Word document or trying to manage a database with sticky notes. Recognizing when you need to upgrade your toolkit is a sign of maturity and career growth.

Furthermore, in online strategy and content creation, the “tools” are your platforms and software. Using a tool designed for one thing (like a personal profile) to achieve a different goal (like enterprise analytics) is often as ineffective as painting with a vegetable. You might get some color on the canvas, but it won’t be a masterpiece.

The Solution to the Puzzle

Have you spotted the creative disaster? If you look closely at the woman’s right hand, you will see she is not holding a paintbrush. She is gripping a large, yellow Corn on the Cob. This is the mistake. She is dipping the tip of the corn into blue paint and attempting to smear it onto the canvas.

While corn has a texture, it is certainly not a tool for fine art. It is a food item. The kernels would create a strange, rolling pattern, and the juice from the corn would mix with the paint, likely ruining the archival quality of the work. It is an absurd substitution that highlights the difference between “being creative” and “being ridiculous.”

The visual joke is that she is treating the corn exactly like a brush—holding it by the end, applying pressure—completely ignoring the fact that it is a vegetable destined for a dinner plate, not a gallery wall.

Why This Mistake Matters

Why do we need to train our eyes to catch these things? Because “Context Blindness” is real. We often accept things just because they are in the right place. We accept a person in a suit as an expert, even if they are talking nonsense. We accept a graph in a presentation as fact, even if the axes aren’t labeled. We accept a corn cob as a brush because it’s in a hand that *should* hold a brush.

Breaking this blindness requires critical thinking. It requires you to look at the data (the object itself), not just the metadata (the location of the object). In financial decision making, this means looking at the actual numbers of an investment, not just the glossy brochure or the confident salesperson.

Moreover, it creates a habit of “Verification.” In a digital world filled with deepfakes and manipulated images, the ability to zoom in and say, “Wait, that doesn’t look right,” is a modern survival skill. It protects you from misinformation and scams.

What This Says About You

If you spotted the corn immediately, you are an “Analyst.” You break things down into their components. You aren’t swayed by the overall picture; you scrutinize the parts. You are the person who finds the bug in the code or the error in the budget.

If you focused on the shirtless man or the neon pink bra first, you are a “Social Observer.” You are drawn to human relationships and narratives. You were likely trying to figure out the story between the artist and the model. This makes you great at storytelling and marketing.

If you missed it entirely, you might be a “Holistic Thinker.” You experienced the *feeling* of the art studio—the light, the mood, the creativity—without getting bogged down in the details. While this allows for great appreciation of beauty, remembering to check the tools will help you execute your own visions more effectively.

Enjoyed this challenge?

Try

this tricky puzzle

to test your observation skills.